Two high quality RCTs (Law et al., 2011; Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effect of occupational performance therapy on family empowerment among families of children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV).

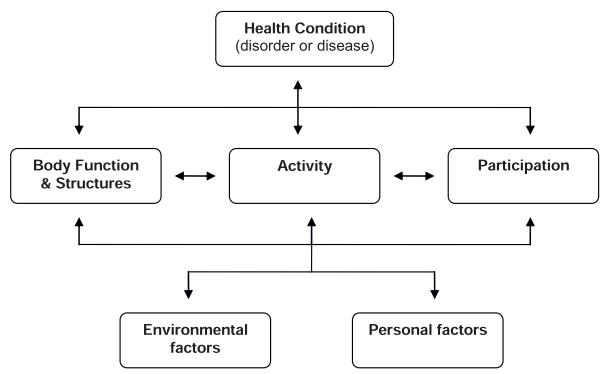

The first high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) randomized patients (GMFCS level I-V) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Family empowerment was assessed using the Family Empowerment Scale (FES; Family, Services, Community) at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

The second high-quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) randomized children (GMFCS level I-IV) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Parent empowerment was assessed using the FES at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is strong evidence (Level 1a) from two high quality RCTs that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than comparison interventions (different occupational performance therapy approaches; regular care) in improving family empowerment among families of children with CP.

One high quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effects of occupational performance therapy on family participation among families of children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV). This high quality RCT randomized patients to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Family participation was assessed using the Family Participation (FP: Daily activities; Personal activities; Sibling activities) at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is moderate evidence (Level 1b) from one high quality RCT that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than a comparison intervention (regular care) in improving family participation among parents of children with CP.

Two high quality RCTs (Law et al., 2011; Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effect of occupational performance therapy on gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV).

The first high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) randomized children (GMFCS level I-V) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Gross motor function was assessed using the Gross Motor Function Measure-66 (GMFM-66) at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

The second high quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) randomized children (GMFCS level I-IV) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Gross motor function was assessed using the GMFM-66 at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group difference was found.

Conclusion: There is strong evidence (Level 1a) from two high quality RCTs that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than comparison interventions (different occupational performance therapy approaches; regular care) in improving gross motor function in children with CP.

Two high quality RCTs (Law et al., 2011; Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effect of occupational performance therapy on mobility in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV).

The first high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) randomized patients (GMFCS level I-V) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Mobility was assessed using the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI: Mobility – Functional Skill Scale; Mobility – Caregiver Assistance Scale) at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). A significant between-group difference was reported in one measure of mobility (PEDI: Mobility – Caregiver Assistance Scale) at follow-up (9 months), favoring child- vs. context-focused approach.

The second high quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) randomized children (GMFCS level I-IV) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Mobility was assessed using PEDI (Mobility – Functional Skill Scale; Mobility – Caregiver Assistance Scale) at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is conflicting evidence (Level 4) from two high quality RCTs regarding the effects of occupational performance on mobility in children with CP. While one high quality RCT found that a child-focused approach was more effective than a context-focused approach, another RCT did not find significant between-group differences.

Note: Difference studies’ power might explain the difference in findings, where Law et al., (2011) involved a larger sample size than Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., (2016) (i.e., n=146 vs. n=68). In addition, Law et al., (2011) provided a 9-month follow-up assessment, whereas Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., (2016) did not evaluate participants at follow-up.

Two high quality RCTs (Law et al., 2011; Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effect of occupational performance therapy on self-care in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV).

The first high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) randomized patients (GMFCS level I-V) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Self-care was assessed using the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI: Self-care – Functional Skill Scale; Self-care – Caregiver Assistance Scale) at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). No between-group differences were found.

The second high-quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) randomized children (GMFCS level I-IV) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Self-care was assessed using the PEDI (Self-care – Functional Skill Scale; Self-care – Caregiver Assistance Scale) at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is strong evidence (Level 1a) from two high quality RCTs that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than comparison interventions (different occupational performance therapy approaches; regular care) in improving self-care in children with CP.

Two high quality RCTs (Law et al., 2011; Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effect of occupational performance therapy on participation in daily life activities in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV).

The first high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) randomized patients (GMFCS level I-V) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Participation in everyday activities was assessed using the Assessment of Preschool Children’s Participation (APCP: Play; Skill development; Active physical recreation; Social activities) at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

The second high-quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) randomized children (GMFCS level I-IV) to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Participation in daily life activities was assessed using the APCP (Play; Skill development; Active physical recreation; Social activities) at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is strong evidence (Level 1a) from two high quality RCTs that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than comparison interventions (different occupational performance therapy approaches; regular care) in improving participation in daily life activities in children with CP.

One high quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effects of occupational performance therapy on parental distress in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV). This high quality RCT randomized patients to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Parental distress was assessed using the Nijmeegse Ouderlijke Stress Index post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group difference was found.

Conclusion: There is moderate evidence (Level 1b) from one high quality RCT that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than a comparison intervention (regular care) in improving parental distress among parents of children with CP.

One high quality RCT (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016) investigated the effects of occupational performance therapy on quality of life in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (all types, GMFCS level I-IV). This high quality RCT randomized patients to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure), a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment) or regular care. Quality of life was assessed using the Question of Quality-of-Life Scale at post-treatment (6 months). No significant between-group difference was found.

Conclusion: There is moderate evidence (Level 1b) from one high quality RCT that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than a comparison intervention (regular care) in improving quality of life in parents of children with CP.

One high quality RCT (Law et al., 2011) investigated the effects of occupational performance therapy on lower extremities’ range of motion in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (GMFCS level I-V). This high quality RCT randomized patients to receive a child-focused approach (remediation of the child’s abilities by changing the components of body function and structure) or a context-focused approach (functional performance remediation by changing constraints regarding the task and/or the environment). Range of motion (left/right: hip abduction/extension, popliteal angle, and ankle dorsiflexion) was assessed using standardized methods at post-treatment (6 months) and follow-up (9 months). No significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: There is moderate evidence (Level 1b) from one high quality RCT that occupational performance therapy is not more effective than a comparison intervention (different approaches of occupational performance therapy) in improving lower extremities range of motion in children with CP.